For a while now I have been wondering how people go about making art, specifically in coming up with imagery. I would say I have lost track of how to make art, although I cannot remember when (if at all) I did know. I do know, though, that I was never unconscious about this topic.

What I mean is that when observing others, which of course operates by assumption, people seem very immersed in their image-making. A lot of people come up with something immediately and on-the-spot, although not everyone does this. I have always been impressed with those who can doodle something when told to. I cannot do this and have never been able to do this.

But I realize that when going about my projects in art school so far, I haven't really "waited until inspiration struck" either. I wait, I just don't remember inspiration. I sit down, I think by way of writing some things down, and the planning stage comes about in the form of a line-by-line succession of notes, bullet points, or statements. This leads to this, to that, and that explains that part, which means its this... and then I stumble into an image somehow.

The reasoning for the art is realized prior to making it (although the more "psychoanalytic" facts and reasonings about the art still come later, if that matters). I create the art's logic before the art is crafted.

I think the image exists as only a sense, though. I never picture something clearly in my head, even though I would be entirely able to. I know I purposefully leave things open, I enjoy generating the image while drawing it. I need to decide on things only after observing instances within the process. Plus, I think openness has its advantages.

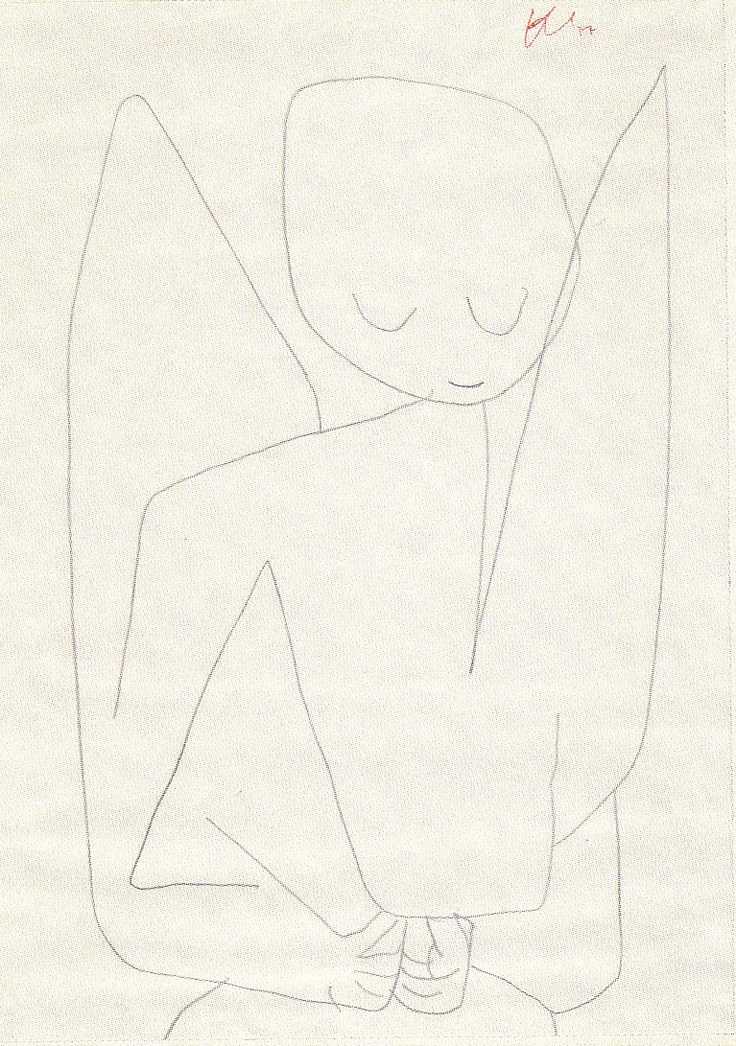

|

| the architectural structures depended on which marks where already made |

It is the way of the stereotypical painter that fascinates me because I am not one. I have an easier time coming up with architectural imagery. It's not that I don't know how to draw anything else, I just struggle to make anything else into an image-scene (an architectural drawing becomes an interactive 3D model/space in my head). If I set about drawing a person, I draw a person, and then it ends quite quickly. I don't know how to merge the object or person into a space. I only know space itself.

Or, it isn't about what I know/don't know, but that anything else results in something different. I fear I have a tendency to become illustrative far too quickly, which is why I don't consider myself as sophisticated or fine-artsy as most people (and I don't want to make illustrations, so I think this is a flaw of mine). I can merge space with object/person, but it becomes illustration. That is why I am constantly asking how to be a painter.

Painters I've observed just get "so into" their process and image, with such a level of certainty, but appear pretty unaware of what's going on. I mean that they are unconscious in a good way. Immersion surrenders the act of stepping-back and viewing something objectively or critically. I suppose this is why people can overwork an image, or get too stuck on one part, or not see something others can.

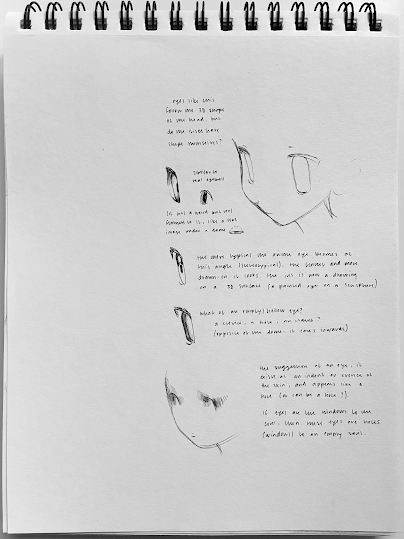

If we treat overworking or lack-of-seeing as symptoms, then it becomes strange, because I have memories of doing those things prior to college. Back in high school, when no one properly took art seriously, but we all believed we were doing something vaguely serious, and everyone worried about "same face syndrome" and made jokes about the "pain" of learning anatomy because we thought those were the things you were supposed to worry about. However, if I think about the very few art assignments I made in high school, I was distinctly not immersed in them, save for the moments where I got lost in the process of repetitive crosshatching (is this the only time I was immersed? Where I remember the "symptoms"?).

And I think I should make a quick confession about the fact that I would draw anime art starting at age 10, and just about any drawing in this I was extremely immersed in, particularly in digital art. But this is shameful, and it actually goes nowhere, so I'm scrapping it aside (although the topic of the digital work field/space is interesting and I would like to get to that sometime).

I must go farther back and think about childhood. I remember the first time I decided to draw from life; I think I had seen some still-life in the museum and developed an inkling on how it was made (I had no idea what art terms meant). Before then, I had been pausing the television and copying it. While watching television, I would watch the outline of each cartoon character, and I would envision curving one of those rubber dividers used in landscaping (I saw my neighbors redo theirs and was fascinated by them, for some reason) to make the outlines.

And after this saga, I lost the desire to ever draw something made up without knowing why (in hindsight, it was traded for making my own anime drawings).

Prior to it, like any kid, I did make imaginative drawings. I remember the process for these well: I had an idea and thought I should draw it, and so I drew whichever "thing" was in my head, and the more narrative the idea was, the more I developed a scenery around it. I often made stories along with my drawings and made my mom write them down on the backside. In particular, because they were the drawings I liked making the most, I drew a lot of robots, though none of them were ever placed in a space. My mom assumed there was a story to these too, so there is a page somewhere where I claim a robot's ability was to clean the house and take out the trash (I like to think I said this to amuse my mom, which worked), but I remember this being very forced, and the robots held a special place in my mind in some manner.

Basically the process is as follows: some pre-held sense or idea; depiction of the main subject or an outline of the scene; development of subjects; determining interaction between subjects; depiction and development of these interactions; continue until a completed scene.

When I force myself to sit down and draw, which was an exercise of sorts in response to my lack of imaginative image-making, I struggle to have any idea at all of what to draw. But when I begin on this process, it goes quite quickly, and the result always surprises me. When I look at the image, I can see how I created its own space/world and where everything falls into place within it, even if it's just a simple sketch.

|

| the left hand (the pointed finger touching the palm) is the most visceral to me, because it was the most visceral to make |

The only thing I know that happens when I drew this, was "this hand goes here, and it touches this (draws 2nd hand), and it's part of the body so..." It's a lot of 'this and so' instead of 'this means that because.' So I wouldn't say it's the subconscious taking over or anything because I am aware of something and using some sort of logic while making it; I'm just not aware from a third-person or twice-detached perspective. Logic is possible in immersion. It's the logic of the image. Immersion lacks critical logic? It's similar to tunnel vision, isn't it?

***

Of the older painters: how does one go about making up a portrait or landscape? Where and what is the difference in process between making up a portrait/landscape from life, and making up depictions of myths, religious scenes, or just scenes that don't exactly exist in real life? And if it is a more straightforward process (painting a portrait of someone and depicting them as they are), is this less substantial or interesting? I am hinting that people do not find this less substantial, so I am asking why so, and where is the substantialness located.

And then I go right back to thinking about art school. Assuming we have gone over the serious of questions about if this or that kind of art is better, and landing on the easy answer that 'no, nothing is better or worse, at least inherently', but then adding a footnote of 'the more revolutionary or innovative are more interesting, yes', I have to ask what art students are doing (because that is my world; you could ask of professional artists, but that's not my world, and sometimes they get into such a rhythm of making their signature art that you need to observe them in a different manner).

Why do my painting classmates make the paintings they make? What do they think about? How do they come up with these images? I have never asked directly because it doesn't ever come up; I did attempt to ask a classmates who is actually part of visual communications why she made her project, how she went about the idea, what interested her, etc. (it was a book containing anonymous replies to a question about their first love experiences). She didn't really answer. Anytime this sort of question is asked in a class, people are a bit baffled, as if they were asked something they thought was common sense.

Of course I can say that this means I'm not a real artist, and it's probably true. But I still want to have an answer. This also doesn't mean that I think people should explain everything, or have their art be explainable. I have had classmates who make such strange art in such strange, immediate, spontaneous ways, that no one questions them because this strangeness becomes its own explanation.

The closest I've gotten to the location of this question/topic is when people explain the emotion behind their art, or the emotion they put into it. I mean that quite frequently people explain the reasoning behind repetitive motifs in their art, for instance, in terms of concept (no surprise in a conceptual school), but this is a step that occurs after the art. It is located in the after, even if its contents take place elsewhere (the motif occurs during the art, the reasoning before and outside of the art), it is an analysis. I am asking about what occurs in the before (and inside, not outside).

This question is especially true for those who feel so strongly about their artmaking and do things with such a high level of confidence or belief (not that they cannot be self-conscious or doubtful at the same time). I want to see what they are seeing, or see what they are thinking (or think what they are thinking? think in the manner of how they are thinking?)

I haven't really reached any conclusion or real question in this post.